F# has a rich and mature development scene for both client- and server-side web programming. Fable revolutionized the durability with which you can craft client-side code, providing F#'s steadfast type system and an MVU programming model. On there server, Giraffe, Saturn and Falco each offer their own unique way of providing similar durability.

DECEMBER 8, 2020

The focus of this post is going to be the Falco Framework, where will aim to build a small, but complete-ish bullet journal using .NET 5.x and ASP.NET Core.

The final solution can be found here if you'd like to follow along that way.

We'll be bringing in a couple of other packages to help us get the job done as well:

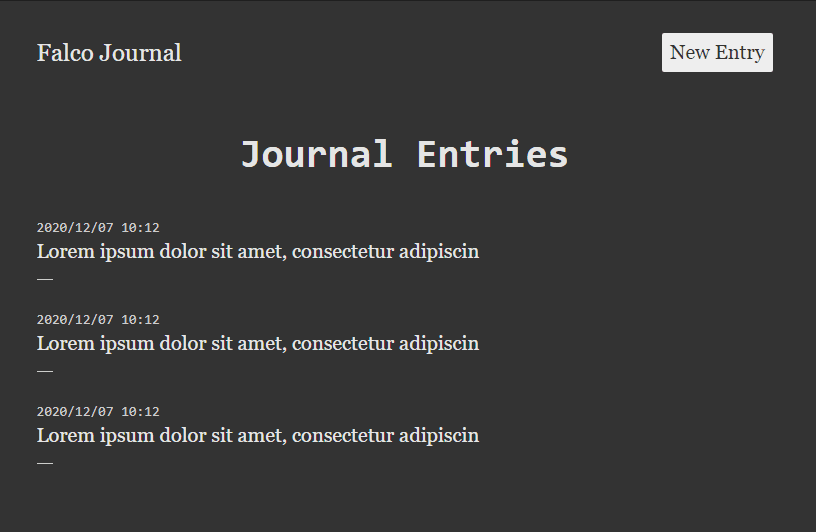

The final app will look something like:

Our bullet journal has a dead simple domain, since we effectively only have one entity to concern ourselves with, a journal entry. But this is great because it will let us focus most of our energy on the web side of things.

To encapsulate our journal entry we'll need to know a few things, 1) the content, 2) when it was written and 3) a way to look it up in the future.

In F# it will look something like:

module FalcoJournal.Domain

open System

type Entry =

{ EntryId : int

HtmlContent : string

TextContent : string

EntryDate : DateTime }

With the definition taking a similar shape in SQL:

CREATE TABLE entry (

entry_id INTEGER NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY

, html_content TEXT NOT NULL

, text_content TEXT NOT NULL

, entry_date TEXT NOT NULL

, modified_date TEXT NOT NULL);

Notice the addition of

modified_datehere. We've purposefully omitted this from the F# model since we don't want the app to exude any control over this. But it will come in useful later for intraday sorting.

Another thing we'll want to model is the state changes of our entry, which will take the form of either 1) creating a new entry, or 2) updating existing entry. I like this approach, despite it involving some duplicate code, because it uses the type system to make our intent clear and more importantly prevents us from filling meaningful fields with placeholder data to knowingly ignore.

module FalcoJournal.Domain

open System

// ...

type NewEntry =

{ HtmlContent : string

TextContent : string }

type UpdateEntry =

{ EntryId : int

HtmlContent : string

TextContent : string }

It's important to stop here for a minute and appreciate that these two entities represent points of input from the user. This means it would likely be wise of us to put some guards in place to ensure that data follows the shape we expect it to. To do this we'll run input validation against the raw input values, using Validus.

Our goal will be to:

module FalcoJournal.Domain

open System

// ...

type NewEntry =

{ HtmlContent : string

TextContent : string }

// equally valid to make this a module function

static member Create html text : ValidationResult<NewEntry> =

let htmlValidator : Validator<string> =

// ensure the HTML is not empty, and check for empty <li></li>

// which is the default value

Validators.String.notEmpty None

<+> Validators.String.notEquals "<li></li>" (Some (sprintf "%s must not be empty"))

let create html text =

{ HtmlContent = html

TextContent = text }

create

<!> htmlValidator "HTML" html

<*> Validators.String.notEmpty None "Text" text

type UpdateEntry =

{ EntryId : int

HtmlContent : string

TextContent : string }

// equally valid to make this a module function

static member Create entryId html text : ValidationResult<UpdateEntry> =

let create (entryId : int) (entry : NewEntry) =

{ EntryId = entryId

HtmlContent = entry.HtmlContent

TextContent = entry.TextContent }

// repurpose the validation from NewEntry, since it's shape

// resembles this and also check that the EntryId is gt 0

create

<!> Validators.Int.greaterThan 0 (Some (sprintf "Invalid %s")) "Entry ID" entryId

<*> NewEntry.Create html text

Now, this adds a fair chunk of code to our previous slim domain. But I'll argue it's worthwhile it for it to live here on the basis that this code is highly cohesive with the type and may end up being used in more than one place.

Validus comes with validators for most primitives types, which reside in the Validators module. They all share a similar function definition, excluding config params. Using some loose F# pseudo-code:

Validators.Int.greaterThan {minValue} {validation message}

// int -> ValidationMessage option -> Validator

ValidationMessage {fieldName}

// string -> string

Validator {fieldName} {value}

// string -> 'a -> ValidationResult<'a>

Validators can be composed using the <+> operator, or Validator.compose. This is demonstrated above in the let htmlValidator : Validator<string> = ... which combines two string validators, including a custom message for the case of an empty <li></li>.

Next on our list are some of the UI elements that will be shared amongst our handlers, including things like buttons, form fields, the layout, top bar and error summary. We'll be using tachyons atomic CSS library since it's lovely for rapid UI development.

Note that to save some space we won't be outlining all of the UI elements in the post. But the full source can be found in final repository.

A core feature of Falco is the XML markup module. It can be used to produce any form of angle-bracket markup (i.e. HTML, SVG, XML etc.).

Most of the standard HTML tags & attributes have been built into the markup module, which are pure functions composed into well-formed markup at run time. HTML tag functions are found in the Elem module, attributes in the Attr module. For string literal output there are several functions available in the Text module.

Elem.div [ Attr.class' "bg-red" ] [ Text.rawf "Hello %s" "world" ]

Rumor has it that the Falco creator makes a dog sound every time he uses Text.rawf.

Note: I am the creator, and this is entirely true.

Idiomatic usage of the Markup module will involve building yourself a suite of project-specific functions for shared UI elements/sections/components. Doing this will drastically simplify the markup code in the feature layer(s).

To demonstrate how this might look, the code below shows some of the common UI elements in our app.

The important takeaway is how extensible having a view engine comprised of pure functions is. End-of-the-line elements, like the pageTitle below, drastically simplify the API for creating the specific chunk of markup. Wrapper elements, like the topBar below, show how elegantly we can compose complex view thanks to the recursive structure of the XmlNode type.

module FalcoJournal.UI

open Falco.Markup

module Common =

/// Display a list of errors as <ul>...</ul>

let errorSummary (errors : string list) =

match errors.Length with

| n when n > 0 ->

Elem.ul [ Attr.class' "mt0 pa2 pl4 red bg-washed-red ba br1 b--red" ]

(errors |> List.map (fun e -> Elem.li [] [ Text.raw e ]))

| _ ->

Elem.div [] []

/// Page title as <h1></h1>

let pageTitle (title : string) =

Elem.h1 [ Attr.class' "pb3 code tc white-90" ] [ Text.raw title ]

/// Top bar with pluggable actions

let topBar (actions : XmlNode list) =

Elem.header [ Attr.class' "pv4" ] [

Elem.nav [ Attr.class' "flex items-center" ] [

Elem.a [ Attr.class' "f4 f3-l white-90 no-underline"

Attr.href Urls.index ] [ Text.raw "Falco Journal" ]

Elem.div [ Attr.class' "flex-grow-1 tr" ] actions ] ]

We're going to build ourselves a simple, yet robust data access layer using Donald. For the sake of simplicity, we'll be sticking to a synchronous approach here, which suits us well anyway given our use of SQLite.

The programming model for Donald is simple, build a IDbCommand from a SQL statement and parameter set, and execute against either an IDbConnection or IDbTransaction (for transactional scenarios). Given that the operation is occurring against a medium with side effects, the return type is always of DbResult<'a>.

To make the development process easier, I find it very useful to devise a "log and pass-through" function for DbResult<'a> (which conveniently returns the full statement and exception thrown):

Fun fact: Unlike ADO.NET, Donald will return field-specific errors when they occur. Providing not only the full statement, but also the specific field which caused the error.

module FalcoJournal.Provider

open System.Data

open Donald

open Microsoft.Extensions.Logging

open FalcoJournal.Domain

// ...

module private DbResult =

/// Log DbResult, if error, and return

let logError (log : ILogger) (dbResult : DbResult<'a>) : DbResult<'a> =

match dbResult with

| Ok _ -> dbResult

| Error ex ->

log.LogError(ex.Error, sprintf "DB ERROR: Failed to execute\n%s" ex.Statement)

dbResult

// ...

With this in place, we're ready to write some data access code. Again, to save time and space only a single example will be shown here. But the full source can be found in the repository.

module FalcoJournal.Provider

open System.Data

open Donald

open Microsoft.Extensions.Logging

open FalcoJournal.Domain

// ...

module EntryProvider =

type Get = int -> DbResult<Entry option>

let get (log : ILogger) (conn : IDbConnection) =

fun entryId ->

let sql = "

SELECT entry_id

, html_content

, text_content

, entry_date

FROM entry

WHERE entry_id = @entry_id"

let fromDataReader (rd : IDataReader) : Entry =

{ EntryId = rd.ReadInt32 "entry_id"

HtmlContent = rd.ReadString "html_content"

TextContent = rd.ReadString "text_content"

EntryDate = rd.ReadDateTime "entry_date" }

dbCommand conn {

cmdText sql

cmdParam [ "entry_id", SqlType.Int32 entryId ]

}

|> DbConn.querySingle fromDataReader

|> DbResult.logError log

// ...

Nothing crazy going on here, but a couple of interesting points to discuss. Firstly, you'll notice that we've specified a function type to represent the operation. I enjoy the ergonomics of this approach, since it ultimately becomes the interface between the IO and business layer's.

The other point of note is that the function type contains no trace of the logger or database connection. So why is that? Since these are not concretely required to perform the operation, they aren't the concern of our final consumers. But they're still required, so how to we fulfill this dependency? Partial application of course! And for that, we'll use a composition root to ensure we aren't having to manually manifest these depdendencies each time we want to interact with the database.

My preference for database-bound projects is to only specify how to create new IDbConnection instances in one place. So for that, we'll create a type to represent our connection factory.

type DbConnectionFactory = unit -> IDbConnection

And we'll register an instance of this within our service collection in Program.fs:

module Falco.Program

// ------------

// Register services

// ------------

let configureServices (connectionFactory : DbConnectionFactory) (services : IServiceCollection) =

services.AddSingleton<DbConnectionFactory>(connectionFactory)

// ...

// -----------

// Configure Web host

// -----------

let configureWebHost (endpoints : HttpEndpoint list) (webHost : IWebHostBuilder) =

// ...

let connectionString = appConfiguration.GetConnectionString("Default")

let connectionFactory () = new SQLiteConnection(connectionString, true) :> IDbConnection

// ...

Now this next little bit is completely optional, you can very effectively build Falco apps without doing this. But I love this approach because it gets me away from having to do the lambda-style HttpHandler every time I need access to dependencies, and almost becomes a tiny DSL for doing your business-logic that automatically enriches your IO layer with it's dependencies.

Since we're now in the web-tier so to speak, we can begin to leverage the composable HttpHandler type. In combination with a very simple function definition, we can save ourselves a TON of code repetition in our feature layer. The best part? All of this amazing functionality only costs you 29 lines of code, with comments!

module FalcoJournal.Service

open System.Data

open Falco

open Microsoft.Extensions.Logging

open FalcoJournal.Provider

/// Work to be done that has input and will generate output

type ServiceHandler<'input, 'output, 'error> = 'input -> Result<'output, 'error>

/// An HttpHandler to execute services, and can help reduce code

/// repetition by acting as a composition root for injecting

/// dependencies for logging, database, http etc.

let run

(serviceHandler: ILogger -> IDbConnection -> ServiceHandler<'input, 'output, 'error>)

(handleOk : 'output -> HttpHandler)

(handleError : 'input -> 'error -> HttpHandler)

(input : 'input) : HttpHandler =

fun ctx ->

let connectionFactory = ctx.GetService<DbConnectionFactory>()

use connection = connectionFactory ()

let log = ctx.GetLogger "FalcoJournal.Service"

let respondWith =

match serviceHandler log connection input with

| Ok output -> handleOk output

| Error error -> handleError input error

respondWith ctx

In a nutshell, we define a function type to represent a "service" (i.e. the work to be done) which effectively says "given an input you will either receive a successful result containing output, or an error". It's basic, but powerful. Next, we create an HttpHandler which will manifest our dependencies, inject them into the provided service and based on the response type invoke either a success or failure handler.

With this in place, our final handlers will look like this, instead of each containing the code above.

let handle : HttpHandler =

let handleError input error : HttpHandler = // ...

let handleOk output : HttpHandler = // ...

let workflow log conn input : ServiceHandler<unit, Output, Error> = // ...

Service.run workflow handleOk handleError ()

Still with me? I realize it's been a lot of content to get here, but it's time for the raison d'être. Our app will be responsible for 3 primary actions:

List all journal entries by date descending - GET /

Persistently create a journal entry - GET + POST /entry/create

Persistently update a journal entry - GET + POST /entry/edit/{id}

To do this, we're going to use a feature-based approach and encapsulate each action into it's own module with roughly the following shape:

module FalcoJournal.Entry

module Create =

type Input = // ... (optional)

type Error = // ...

let service : ServiceHandler<'input, 'output, Error> = // ...

let view : XmlNode = // ...

let handle : HttpHandler = // ...

For this post, we'll be covering #2, creating a new journal entry. But, feel free to checkout the full source for the other two endpoints.

When building server-side MPA's (multi-page apps) most actions will come in pairs. A GET to load the initial UI and data, and a POST (or PUT) to handle submissions. Our case will be no exception. First we'll devise the GET handler and a view which will be shared between the pair. Then we'll move on to build the supporting POST action.

GET /entry/createFor this endpoint we know we need a view, and a means of rendering it. Luckily we've already got a working suite of UI utilities to pull from, and Falco comes with everything we need to render it.

open Falco.JournalEntry

// ...

module New =

let view (errors : string list) (newEntry : NewEntryModel) =

let title = "A place for your thoughts..."

let actions = [

Forms.submit [ Attr.value "Save Entry"; Attr.form "entry-editor" ]

Buttons.solidWhite "Cancel" Urls.index ]

let editorContent =

match newEntry.HtmlContent with

| str when StringUtils.strEmpty str ->

Elem.li [] []

| _ ->

Text.raw newEntry.HtmlContent

Layouts.master title [

Common.topBar actions

Common.errorSummary errors

Elem.form [ Attr.id "entry-editor"

Attr.method "post"

Attr.action Urls.entryCreate ] [

Elem.ul [ Attr.id "bullet-editor"

Attr.class' "mh0 pl3 outline-0"

Attr.create "contenteditable" "true" ] [

editorContent

]

Elem.input [ Attr.id "bullet-editor-html"

Attr.type' "hidden"

Attr.name "html_content" ]

Elem.input [ Attr.id "bullet-editor-text"

Attr.type' "hidden"

Attr.name "text_content" ]

]

]

let handle : HttpHandler =

view [] NewEntryModel.Empty

|> Response.ofHtml

Some of this should already be familiar from our discussion in the UI section, specifically the Common.topBar and Common.errorSummary. We've also introduced a few other UI elements, most notably our master layout (Layouts.master) and button elements (Button.solidWhite).

You'll notice that our view function takes a NewEntryModel as it's final input parameter. This leads into one of the main benefits of using the Falco markup module as an HTML view engine, strong typing. If the definition of NewEntryModel (seen below) changes in a breaking way, you better believe the compiler will tell you about it, and this is a great thing. Just think of all the bugs this can save!

The actual handler in this case is pretty straight-forward. It simply invokes the view with an empty error list and empty model, and passes it into the Falco Response.ofHtml handler.

Defining a static member for creating an empty record like this,

NewEntryModel.Empty, is a pattern I like to keep my code clutter free.

POST /entry/createThe POST aspect of our pairing is a little more interesting, requiring us to define error states, a service and wire up our dependencies. In order to obtain the user input, we'll also need to model bind the form values submitted and validate them to ensure they meet our criteria. And in the case of submission errors, we'll render the view from the GET action of the pair.

type NewEntryModel =

{ HtmlContent : string

TextContent : string }

static member Create html text =

{ HtmlContent = html

TextContent = text }

static member Empty =

NewEntryModel.Create String.Empty String.Empty

module Create =

type Error =

| InvalidInput of string list

| UnexpectedError

let service (createEntry : EntryProvider.Create) : ServiceHandler<NewEntryModel, unit, Error> =

let validateInput (input : NewEntryModel) : Result<NewEntry, Error> =

let result = NewEntry.Create input.HtmlContent input.TextContent

match result with

| Success newEntry -> Ok newEntry

| Failure errors ->

errors

|> ValidationErrors.toList

|> InvalidInput

|> Error

let commitEntry entry : Result<unit, Error> =

match createEntry entry with

| Error e -> Error UnexpectedError

| Ok () -> Ok ()

fun input ->

input

|> validateInput

|> Result.bind commitEntry

let handle : HttpHandler =

let handleError (input : NewEntryModel) (error : Error) =

let errorMessages =

match error with

| UnexpectedError -> [ "Something went wrong" ]

| InvalidInput errors -> errors

New.view errorMessages input

|> Response.ofHtml

let handleOk () : HttpHandler =

Response.redirect Urls.index false

let workflow (log : ILogger) (conn : IDbConnection) (input : NewEntryModel) =

service (EntryProvider.create log conn) input

let formMap (form : FormCollectionReader) : NewEntryModel =

{ HtmlContent = form.GetString "html_content" ""

TextContent = form.GetString "text_content" "" }

Request.mapForm

formMap

(Service.run workflow handleOk handleError)

Following our pattern from above, the module tells a nice "story" about how it's little world works. We immediately see that we can expect one of two error states, invalid input or an unexpected error (kind of an "error bucket" I understand, but this is a demo app). Next we can see that there will be work potentially done, that requires a NewEntryModel to come in and will either produce no output, unit in the case of success, or an Error in the case of failure which we are forced to deal with thanks to F# completeness.

The service itself defines a single dependency, on EntryProvider.Create, which has been partially applied in our composition root with the ILogger and IDbConnection it requires to perform IO. Two discrete steps are laid out in the service, validating the input & transforming it into our valid domain model, NewEntry, and committing the entry to our database. Finally, we define a simple result-based pipeline to process our input.

The form of the HttpHandler also tells a story that is easy to reason about. If we hide the definitions of the four functions, we can easily see that we have code to: handle errors, handle success, define our workflow and map our form. And truly there isn't much more to it than that.

We kick things off using another function built into Falco called Request.mapForm which takes a mapping function (FormCollectionReader -> 'a) as it's first parameter and an input-bound HttpHandler ('a -> HttpHandler) as a second parameter. In our case, this handler is the function we defined in our composition root, which requires input of type 'a for a service of type ServiceHandler<'a, 'output, 'error>. From here, if the service succeeds, handleOk response by redirecting us back to / and if the service fails we are shown the view with error messages displayed.

Did you know?

Similar to theFormCollectionReader, Falco offers analogous readers for: query strings, headers and route values. All of which allow you to safely and reliably obtain values from these disparate sources in a uniform way.

This post was a ton of fun to write, and yet so difficult to decide upon what content made it in and what didn't. Hopefully my decision making there was on point and this point helps paint a clear picture about developing idiomatic F# web apps using Falco.

If you've used Falco and love it (or hate it) I want to hear from you! I'm usually also available on both Slack and Twitter if you'd prefer to reach me there.